Interview with architectural photographer Dan Alka

Dan Alka

Dan Alka is a Czech architectural, art, and portrait photographer. He worked with Oliviero Toscani for several years and founded the multimedia platform INSTATRIO.com. This helps travelers and architecture enthusiasts discover landmarks and cultural sites worth seeing around the world.

In this interview, Dan Alka talks about his collaboration with WhiteWall, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s concept of the “decisive moment,” the influence of his childhood in the industrial city of Ostrava, and gives tips for beginners in architectural photography.

Can you tell us a little bit about how you became a photographer?

I became a photographer before I ever held a camera. Seeing came first—attention, curiosity, the habit of looking twice. The camera arrived later as an extension of that habit, a way to net the visible while allowing the invisible to leave its trace. What draws me is not only the dance of light, but the emotion suspended in the space around it, the residue of memory, the silence between gestures—the parts of reality that don’t announce themselves but still insist on being felt.

I grew up in Ostrava, an industrial city in Czechia—once one of Europe’s most important coal and steel hubs. My favorite ‘playgrounds’ weren’t parks or sports fields, but the city’s abandoned factories. To most, these brownfields were scars on the urban landscape; to me, they were tangled sculptures—woven networks of steel and flickering light, where rust, geometry, and shadow spoke their own language.

I would wander through their silent corridors, tracing peeling paint, rusty staircases, collapsed floors, dangling wires, and loose bricks. A wrong step could stir asbestos from hidden walls or ceilings, so moving through such places taught me that attention to detail was its own form of seeing.

I returned again and again to observe their evolving shapes, intricate details, and raw textures. Every fragment seemed to spark a new idea, a new way of seeing. Cracks, rust, and twisted metal weren’t just decay—they were catalysts for creativity, invitations to trace new lines, discover hidden patterns, and linger in the interplay of structure and light.

When I first picked up a camera, I was drawn to architecture—not just as a subject, but as a means of exploring the space between what we understand as reality and what exists beyond our perceptions of it. At first, I wandered these abandoned buildings, observing their forms and textures, letting them spark my imagination. But I soon realized that only the camera could preserve and translate these fleeting impressions, giving these silent structures a second life in photographs.

From that early insistence on observing every detail, my guiding principle emerged: “No detail is too small.” Today, whether I’m capturing the stark lines of ultra-modern architecture or the fleeting poetry of light on concrete, I carry that lesson forward, revealing the hidden stories and subtle textures that make each space unforgettable.

How do you get inspired? And what inspires you the most? Films, books, or magazines? Or what surrounds you?

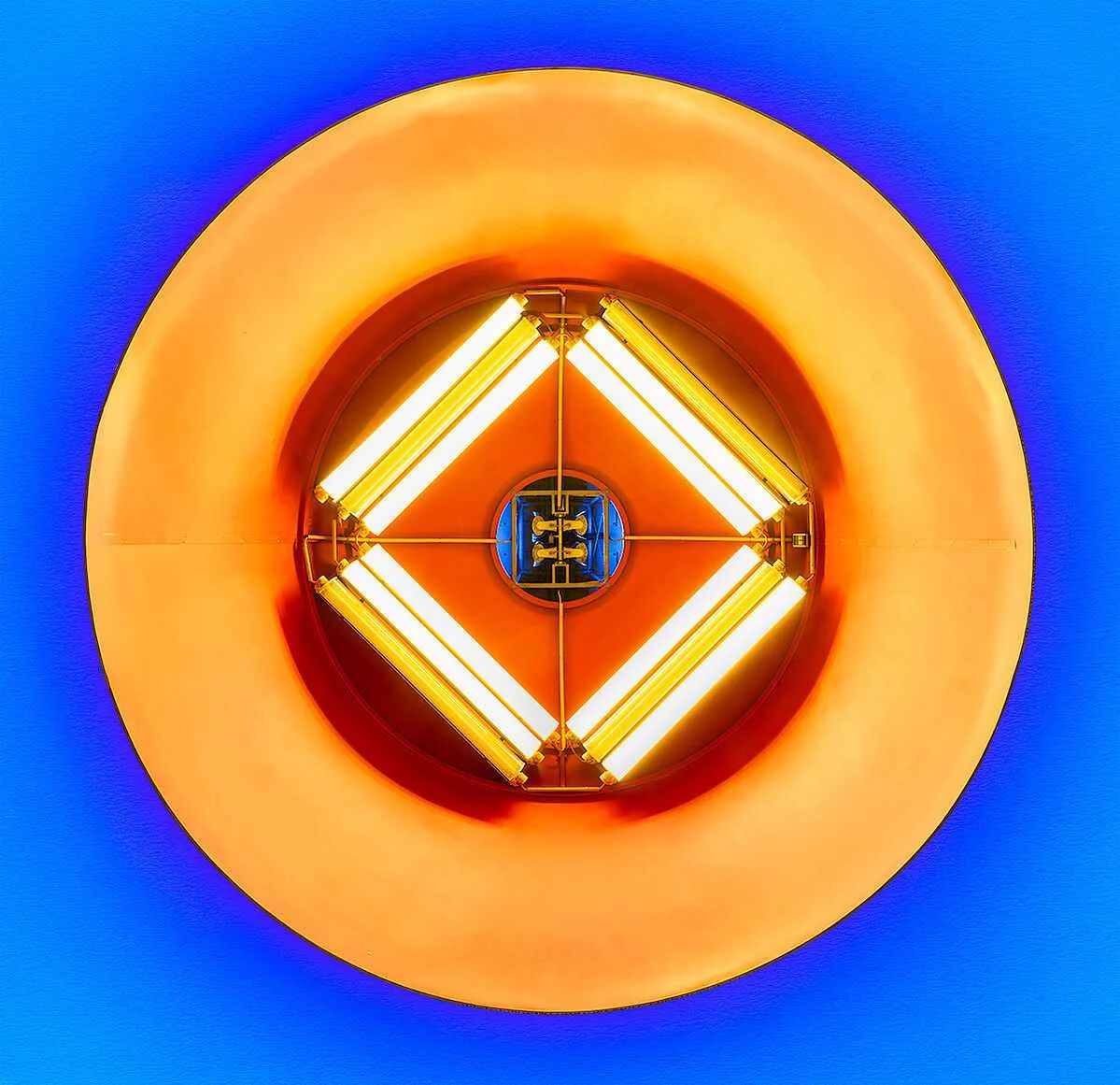

Photo: Dan Alka - The photo print on aluminum Dibond is framed by a gold Aluminum ArtBox. From the front, the frame appears subtle and picks up on the warm colors of the motif. At the same time, the depth of the ArtBox gives the image a sculptural presence.

I don’t believe inspiration is something you have to chase. It’s already everywhere—woven into the curve of a shadow, the texture of a wall, the way light falls on a face you’ve seen a thousand times. The challenge isn’t finding it, but choosing to notice it, to give it your full attention. That’s where the difference lies between looking and seeing: looking is passive, seeing is an act of intent. The moment you truly see, the ordinary world transforms into an endless source of enrichment and wonder.

Photo: Dan Alka

The Great Wave off Kanagawa — Hokusai’s legendary woodblock print, perhaps the most reproduced image in the history of art — became the silent undertow beneath my photograph of what is likely Switzerland’s most photographed building. That wave has pursued me ever since I first stood before the original in a museum.

Your work is characterized by a clear focus on modern architecture. Could you tell us more about your photographic style and how it has evolved over the years?

Architecture, particularly modern structures, is my starting point, but not my destination. Photography, for me, isn’t about capturing what is—it’s about revealing what else it could be.

Over time, I’ve realized that the real growth in my work hasn’t been technical—it’s been philosophical.

Minor White once said, “Don’t just photograph what it is, but photograph what else it is.” This principle guides my work: I don’t use my camera as a mere copy machine or reality scanner—its purpose is to be a window into what I imagine, feel, and envision.

Lao Tzu wrote 2,500 years ago, “The five colors blind the eye.” Limiting the world to fixed categories—what is beautiful, worthy, or photogenic—dims perception. Much of my growth has come from letting go of visual clichés and rigid rules, allowing the world’s hidden textures, shadows, and rhythms to emerge.

Architecture gives me structure, rhythm, and form, but imagination drives my lens. Sometimes I distort, double, or abstract—not to manipulate reality, but to expand it. Through these techniques, I strip away the obvious and reveal the unseen, exploring liminal spaces where perception shifts and familiar forms reveal unexpected nuances.

Photography, for me, is an expression of imagination—a way to communicate not just the physical world, but emotions, thoughts, and abstract ideas. Buildings are not static; they are conversations between light, space, and time.

My mission is to see—and to help others see—not just what is, but what could be.

You’ve already captured many impressive architectural shots. Is there a particular moment in your photographic journey that has been especially formative for you?

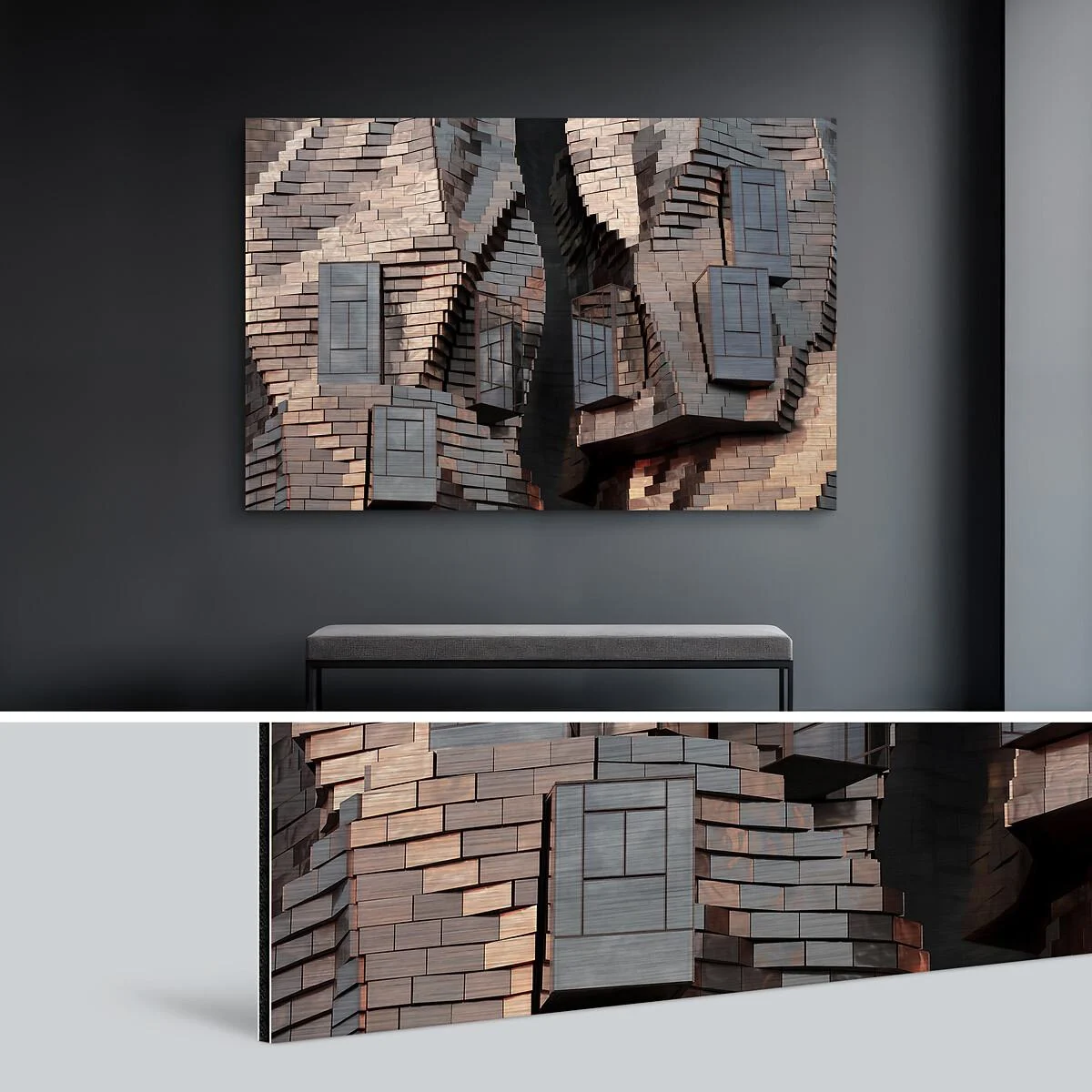

Photo: Dan Alka - Here, the photo print was laminated onto brushed aluminum Dibond, giving the light and white areas of the image a metallic sheen – an effect that impressively emphasizes the structure and materiality of the facade.

The first came in my childhood in Ostrava, a city then cloaked in grey facades, crumbling factories, and even black snow from heavy pollution. The world around me was heavy, suffocating, and visually numb. Then one day, Oliviero Toscani’s Benetton billboards appeared. It felt like a sonic boom in my head: blinding white backdrops pierced by images that carried more power than words: a Black woman nursing a white baby, a priest kissing a nun, a newborn still bound to its cord, three human hearts labeled white, black, yellow, or portraits of prisoners on death row — they struck me deeply.

Equally fascinating were the reactions of people around me. I remember my grandmother’s outrage, her conservative faith colliding with images she couldn’t bear to look at. I realized then that photography could provoke as much as it could illuminate—that it could disturb silence, question and ignite dialogue.

The second moment came years later, when photography had almost slipped out of my life. I was working as an IT consultant in Germany when I attended one of Toscani’s lectures. After his lecture, I approached him, told him what his images had meant to me as a boy, and showed him some photographs of my own. To my astonishment, he not only liked them—he invited me to his studio in Tuscany.

What was meant to be a weekend became three years of collaboration at his side, immersed in his studio, absorbing his way of seeing and questioning. Those years did not just return me to photography—they rewired the way I understood it: not merely as images, but as conversations with the world.

Architectural photography requires a lot of patience and a fine sense for the right angle. How do you approach planning a shoot to capture the perfect image?

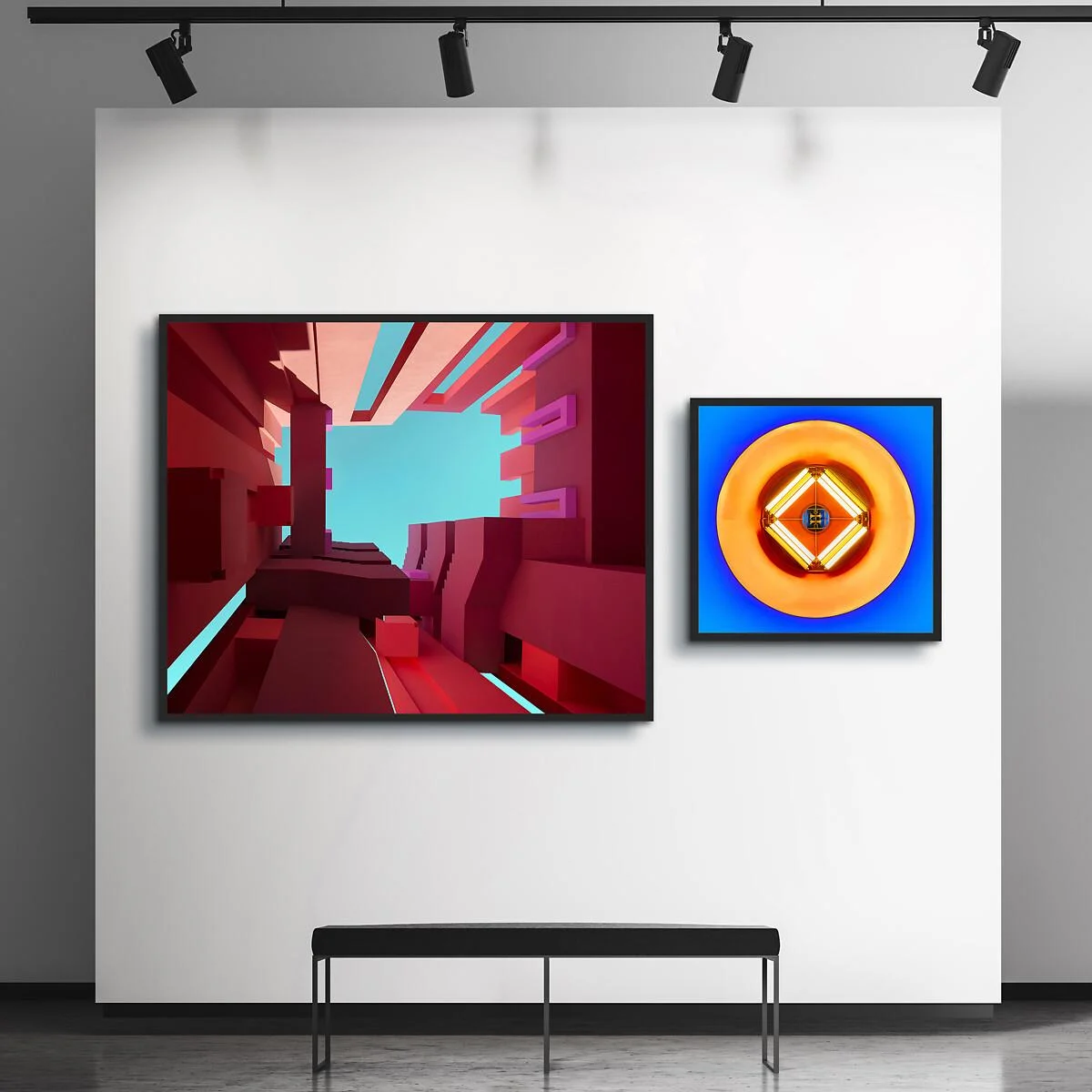

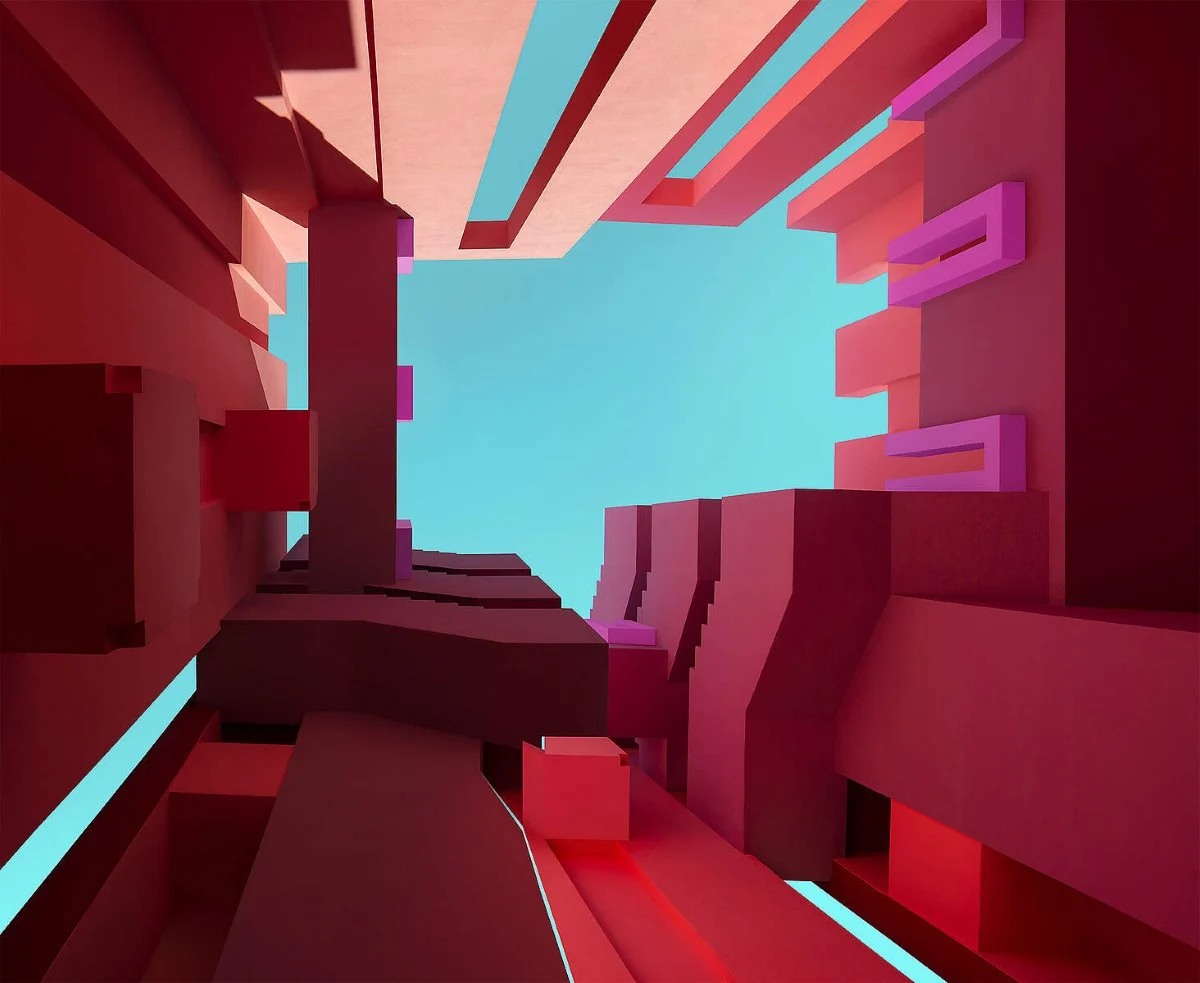

Photo: Dan Alka - The abstract architectural motifs gain depth thanks to the matte acrylic glass and display clear colors with reduced reflections. The black Hamburg frame creates a clear visual boundary, focusing the eye.

“My photography begins long before I arrive on location.”

“I prepare meticulously, yet always leave space for chance.”

Before traveling, I sketch ideas and pore over maps, books, and aerial views of a city. Once there, I immerse myself fully—skating through streets day and night, climbing towers for bird’s-eye perspectives, slipping into hidden interiors, and listening to locals to grasp what it truly feels like to live there.

When I discover a place worth capturing, I return to it again and again, watching how light and weather transform its character. Though impatient by nature, I can wait for days at the same spot, trusting from experience that there is a good chance the moment will arrive. Podcasts and audiobooks keep me company, turning long hours of waiting into something bearable—even enjoyable. My true attention, however, is fixed on that decisive moment—the singular convergence of vision, light, and composition.

For me, photography is always a dialogue between preparation and spontaneity: knowing what I hope to see, yet remaining open to the unexpected. The most compelling images are often born in the tension between intention and serendipity—but this is far from the only path. I like to call an alternative approach the ‘Composed Moment.’

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s more than 70-year-old concept of the “decisive moment” is one of the most famous ideas in photography. It describes the fleeting instant when life aligns spontaneously—gesture, composition, and meaning converging perfectly—so that the photograph feels both inevitable and alive. Achieving it requires patience, observation, and intuition. The decisive moment is discovered, not created; the photographer waits for reality to arrange itself before pressing the shutter.

Sometimes, one must take unconventional routes to find the right subject. Could you share a articular challenge you’ve had to overcome during an architectural shoot?

Photo: Dan Alka

One of the greatest challenges in architectural photography today isn’t the weather, lighting, or even the technical aspects—it’s trust. A tripod can stir more paranoia and suspicion than sympathy. Security guards, residents, and even passersby often assume you have an agenda beyond art.

I particularly remember two cities where obtaining photo permission in advance was a slow and complicated ordeal. In Istanbul, when I went without it, a fully armed unit quickly reminded me I wasn’t welcome to use my camera there. In London—with its extensive network of CCTV cameras—I was quickly spotted before I even found the right spot to set up my tripod.

Over the years, I’ve learned to navigate that tension, becoming better at showing people that I’m not ‘taking’ something, but offering something back: an image, a perspective, a reminder that architecture isn’t just concrete and glass, but a social document. These buildings are part of our collective memory, their shapes carrying the ideals and ambitions of the times that created them.

From your perspective, what are the biggest mistakes beginners make in architectural photography? What tips do you have for avoiding them?

Beginners often rush and get caught up in gear, overlooking one of the most valuable tools: patience, which allows a scene—or a moment—to reveal itself. Look at your surroundings with the curiosity of a child; don’t just see, truly observe. Ask yourself why you make photographs and what you hope to share—technical mastery alone won’t make them resonate. Obsession, presence, and curiosity are what transform a picture from correct to unforgettable.

You’ve already worked with WhiteWall to print some of your works in large formats. How was your experience with the quality and presentation of your work on WhiteWall prints?

I first discovered WhiteWall years ago, while working in Germany, and quickly came to see it as one of the most reliable and professional choices for fine art printing. Over time, I’ve tested many print studios across Europe and beyond, but I have yet to find another that matches WhiteWall’s balance of uncompromising quality and thoughtful service.

What impressed me from the beginning was not only the technical excellence of the prints but also their commitment to making complex processes feel simple, offering a wide range of materials, and ensuring that the experience of ordering large-scale works remains precise and stress-free.

In many ways, WhiteWall reflects one of my own guiding principles as an artist: no detail is too small. Even if unspoken, that shared philosophy is evident in the way they handle every step of the process.

Equally important has been the personal side: WhiteWall has always taken the time to answer questions with care and clarity. I especially want to thank Amanda and Maxine from the Miami and New York teams, whose support has been consistently attentive and genuinely helpful throughout my collaborations with WhiteWall.

Most recently, I ordered four large-scale prints, and I could not be happier with the results. Each piece shows how the right printing approach can unlock a photograph’s full potential—sharpening its presence, amplifying its atmosphere, and turning it into something that truly fills a space. Each of these works was printed using a different technique and material, chosen to best reflect the mood and character of the image. I’ll be sharing those works here, along with the materials and techniques behind them—which, just like I did, you can easily select for each individual photograph on WhiteWall’s site before printing. And if you happen to be in Prague, come see them live at the amazing Showroom Fiala.

When it comes to large-format prints, details and clarity are crucial. What aspects are most important to you when preparing an image for such a large print?

Photo: Dan Alka

When I prepare an image for a large-format print, I try to think beyond pixels and technical precision. For me, it begins with a more fundamental question: what scale does this image truly deserve? Bigger is not always better. Would the Mona Lisa (77 x 53 cm) or Girl with a Pearl Earring (44 x 39 cm) retain their quiet power if enlarged? And conversely, would Guernica (349 x 777 cm) or The Night Watch (380 x 454 cm) keep their force if reduced?

Sometimes a smaller scale lends intimacy, while other times a monumental print amplifies presence and transforms how it is experienced.

I often draw on painting for perspective—art has always shown how scale and composition shape perception, long before the invention of photography. Like those masters, I think carefully about how a viewer’s eye moves, how presence and emptiness interact, and how details reveal themselves only when the piece is fully encountered.

Clarity matters, of course, but scale alone never makes an image powerful. The right size allows subject, composition, and story to resonate fully, transforming a photograph into an immersive, almost cinematic experience. For me, large-format printing is not about technical perfection, but about translating narrative, atmosphere, and emotion into a space the viewer can truly inhabit. Every decision—from framing to final scale—is guided by the experience I hope to create, not by an automatic push to make it ‘bigger.’

Do you have any special tips for photographers who want to print their architectural shots in large formats, to ensure that the details are clearly and precisely captured in larger sizes?

There’s a wonderful article on your site—4 Steps to Large-Format Lamination” by Jan-Ole Schmidt—that beautifully outlines the technical considerations. But I’d like to offer a different kind of advice—something more ephemeral, yet just as essential.

As Ansel Adams once said, “There is nothing worse than a sharp image of a fuzzy concept.” Many technically flawless architectural photographs—tack sharp and perfectly exposed—can still feel sterile if they lack emotional resonance. Sharpness alone doesn't make a compelling image. Conversely, a slightly imperfect photograph can captivate, stir emotion, or spark narrative through mood, movement, or mystery.

Take Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Architecture series, for instance. His blurred representations of iconic buildings don’t aim to document every detail—they aim to evoke. Through intentional softness, Sugimoto distills architecture to its essence: shape, memory, and atmosphere. The results are timeless, dreamlike, and deeply contemplative. We often remember buildings not in crystal-clear lines, but as impressions—moments of light, shadow, and feeling.

So yes—choose the right lens, shoot in RAW, use base ISO, keep your camera steady, set your aperture and shutter speed carefully, correct perspective, and take advantage of tools like tilt-shift lenses or techniques like focus stacking, HDR, or bracketing when needed—along with all the other quiet calculations that go into getting it right. Get comfortable with post-processing in software like Photoshop—or an equally powerful (and free) alternative like Photopea.com, which was created from scratch by my brilliant friend Ivan Kutskir—who developed this powerful software all by himself, an incredible feat considering Photoshop is created by a huge team—estimated at around 100 members.

But don’t lose sight of your voice as an artist. Ask yourself: What story am I telling? What feeling do I want to leave behind? Because in the end, a photograph that lingers in someone’s memory usually has more to do with its soul than with its sharpness. Technical perfection is a tool—not the goal. Your viewers won’t remember the noise or the slight blur; they’ll remember how the image made them feel.

What else should we know about you?

Photo: Dan Alka

I work daily on my web and multimedia project, INSTATRIO.com, which features a carefully curated collection of the finest photographs, videos, audio, texts, and an interactive map. Though still in its beta phase, INSTATRIO.com already showcases several hundred MUST-SEE places around the world and serves as a quick, practical tool for discovering and planning visits to unforgettable destinations. INSTATRIO.com helps you search less by offering a curated collection of must-see places, so you can discover more effortlessly.

The project’s motto is “SEARCH LESS, DISCOVER MORE.” As an ongoing labor of love, I continuously add new places and enrich the content.

In the future, I plan to expand INSTATRIO.com into a collaborative platform, inviting selected fine art photographers and videographers worldwide to contribute.

Follow my Instagram profile @danalka_com for the latest updates and news about the project’s development.

WhiteWall Product Recommendations

You might also like these articles:

Submitted by WhiteWall Team

Interview with Ksenia Felker - Analog aesthetics rediscovered

Ksenia Felker discovers the beauty of the moment in analog photography. In this interview, she talks about her love of light, shadow, and quiet scenes, the mindfulness behind each image, and why it is precisely this slow pace that makes her art so special.

Submitted by WhiteWall Team

Happy Sad Places – Interview with Paul Hiller

Pastel-colored architecture, colorful amusement rides, and obscure roadside attractions. For more than 15 years, Paul Hiller has been photographing these curious places around the world, capturing his so-called Happy Sad Places.

Submitted by WhiteWall Team

Architectural world of color by Paul Eis

Berlin-based photographer Paul Eis stages classical architecture through photography, mixes different styles, and digitally processes his photos into intense worlds of color.